Hattusa: The Ancient Capital of The Hittites

One of Turkey’s

lesser visited but historically significant attraction is the ruin of an

ancient city known as Hattusa, located near modern Boğazkale within the

great loop of the Kızılırmak River. The city once served as the capital

of the Hittite Empire, a superpower of the Late Bronze Age whose

kingdom stretched across the face of Anatolia and northern Syria, from

the Aegean in the west to the Euphrates in the east.

The Hittite

Empire is mentioned several times in the Bible as one of the most

powerful empires of the ancient times. They were contemporary to the

ancient Egyptians and every bit their equal. In the Battle of Kadesh,

the Hittites fought the mighty Egyptian empire, nearly killing Pharaoh

Ramses the Great, and forcing him to retreat back to Egypt. Years later,

the Egyptians and the Hittites signed a peace treaty, believed to the

oldest in the world, and Ramses himself married a Hittite princess to

seal the deal.

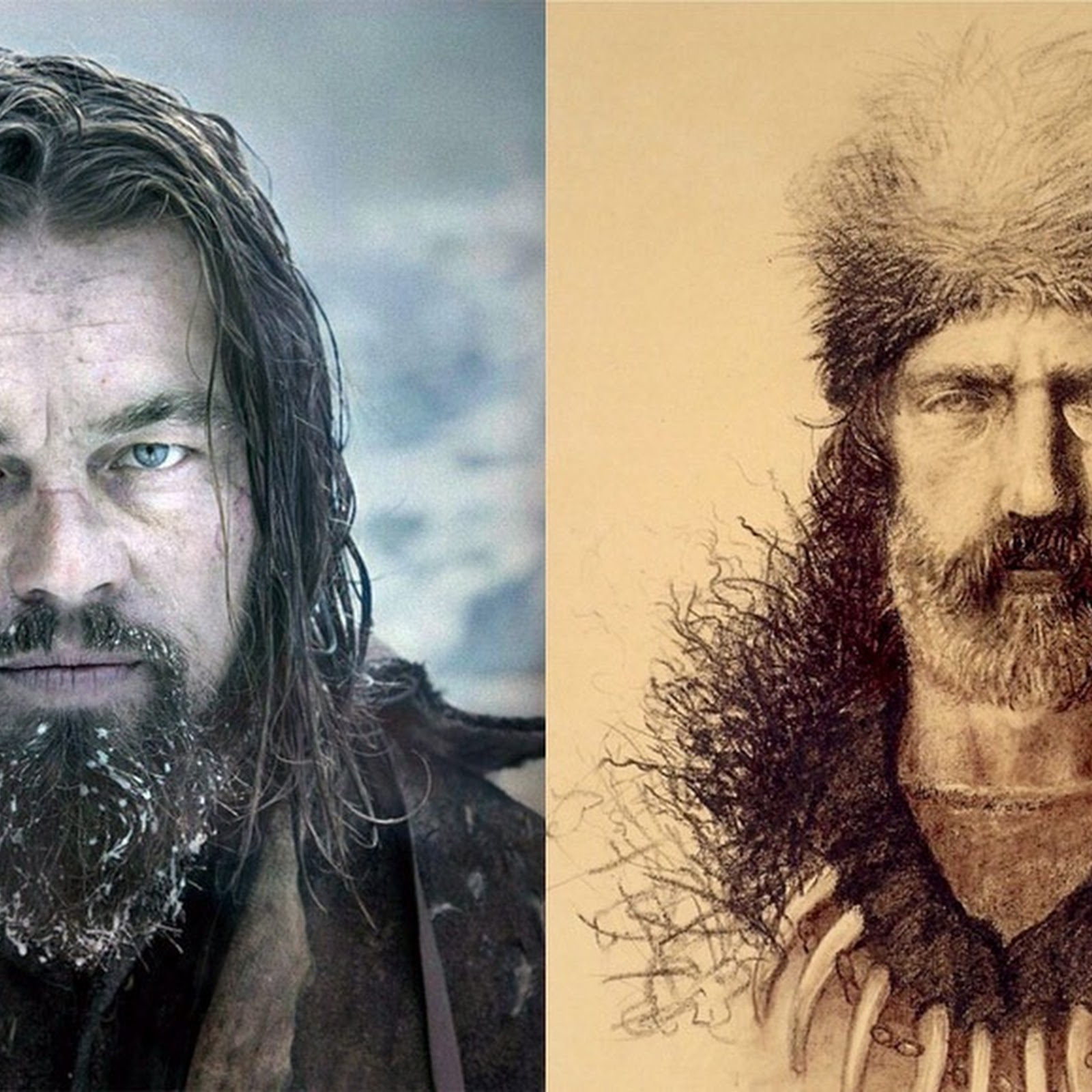

Hattusa during its peak. Illustration by Balage Balogh

Hattusa during its peak. Illustration by Balage Balogh

The

Hittites played a pivotal role in ancient history, far greater than

they are given credit for in modern history books. The Hittites

developed the lightest and fastest chariots in the world, and despite

belonging to the Bronze Age, were already making and using iron tools.

Incredibly,

until as recently as the turn of the 20th century, the Hittites were

considered merely a hearsay since no evidence of the empire’s existence

was ever found. This changed with the discovery and excavation of

Hattusa, along with the unearthing of tens of thousands of clay tablets

documenting many of the Hittites' diplomatic activities, the most

important of which is the peace settlement signed after the Battle of

Kadesh between the Hittites and the Egyptians in the 13th century BC.

Hattusa

lies at the south end of the Budaközü Plain, on a slope rising

approximately 300 meters above the valley. It was surrounded by rich

agricultural fields, hill lands for pasture and forests that supplied

enough wood for building and maintaining a large city. The site was

originally inhabited by the indigenous Hattian people before it became

the capital of the Hittites sometime around 2000 BC.

Hattusa was

destroyed, together with the Hittite state itself, in the 12th century

BC. Excavations suggest that the city was burnt to the ground, however,

this destruction appears to have taken place after many of Hattusa’s

residents had abandoned the city, carrying off the valuable objects as

well as the city’s important official records. The site uncovered by

archaeologists was little more than a ghost town during its final days.

At

its peak, the city covered 1.8 square km and comprised an inner and

outer portion, both surrounded by a massive and still visible course of

walls, the outer of which ran for 8 kilometers surrounding the whole

city. The inner city was occupied by a citadel with large administrative

buildings and temples. The royal residence, or acropolis, was built on a

high ridge.

To the south lay an outer city of about 1 square km,

with elaborate gateways decorated with reliefs showing warriors, lions,

and sphinxes. Four temples were located here, each set around a

porticoed courtyard, together with secular buildings and residential

structures. Outside the walls are cemeteries, most of which contain

cremation burials. Between 40,000 and 50,000 people is believed to have

lived in the city at the peak.

Lion Gate in Hattusa. Photo credit:

Bernard Gagnon/Wikimedia

King's Gate in Hattusa. Photo credit:

turkisharchaeonews.net

Sphinx Gate in Hattusa. Photo credit:

Bernard Gagnon/Wikimedia

A modern full-scale reconstruction of a section of the wall surrounding Hattusa. Photo credit:

Maarten/Flickr

The

Egyptian–Hittite peace treaty, on display at the Istanbul Archaeology

Museum. It is believed to be the earliest example of any written

international agreement of any kind. Photo credit:

yasin turkoglu/Flickr

Panoramic view of the Lower City of Hattusa. Photo credit:

turkisharchaeonews.net

Processional way of the Grand Temple complex, Hattusa. Photo credit:

turkisharchaeonews.net

Royal Citadel in Hattusa. Photo credit:

turkisharchaeonews.net

Entrance to a stone tunnel called the Yerkapı, in Hattusa. Photo credit:

turkisharchaeonews.net

Yerkapı in Hattusa. Photo credit:

turkisharchaeonews.net

The Yerkapi rampart at Hattusa. Photo credit:

turkisharchaeonews.net

Sources:

Wikipedia /

Ancient Wisdom /

UNESCO /

Biblical Archaeology

Subscribe to our Newsletter and get articles like this delivered straight to your inbox