Makhunik: The Village of Dwarves

In a remote corner in Iran’s South Khorasan Province, near its border with Afghanistan, is a village that, until about a century ago, was inhabited by people of very short stature. Indication of their dwarfism is found in the local architecture. Of the roughly two hundred stone and clay houses that make up the ancient village, seventy or eighty of them are of exceptionally low height. These adobe dwellings are less than two meters tall with narrow doorways that cannot be entered without stooping. Some of these houses have ceiling as low as 140 cm.

Marriages between close relatives, poor diet and drinking water laced with mercury had left the residents of Makhunik a good half a meter short than the average height of that time.

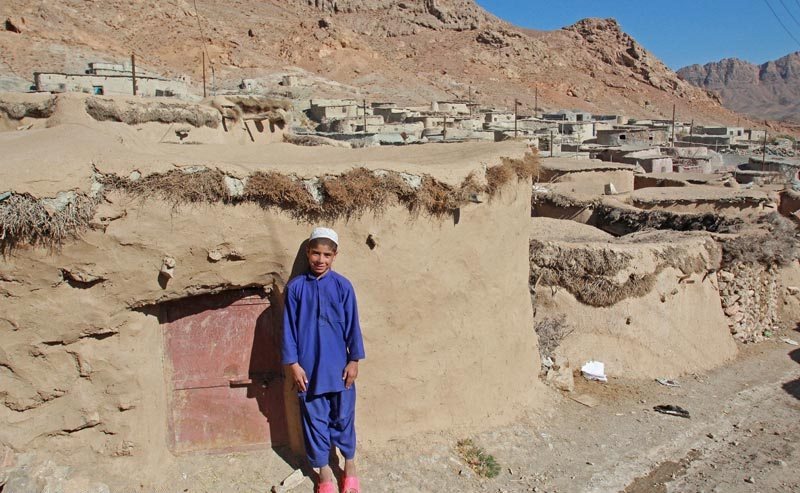

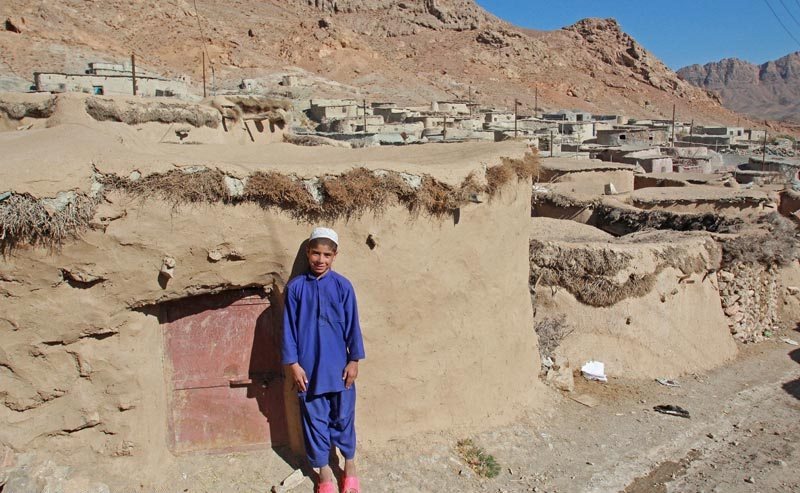

A boy stands in front of a tiny house in the village of Makhunik, in Iran. Photo credit: tripyar.com

For centuries, Makhunik’s ancestors lived in almost complete isolation from modern civilization. The region was dry, desolate and barren that made growing crops and keeping animals difficult. Turnips, grain, barley and a date-like fruit called jujube constituted the only farming. People survived on simple vegetarian dishes such as kashk-beneh (made from whey and a type of pistachio that is grown in the mountains), and pokhteek (a mixture of dried whey and turnip).

Malnutrition contributed significantly to the residents’ height deficiency. The isolation also forced people to marry among close relatives allowing bad genes shared by both parents to be expressed more pronouncedly in their offspring. Some of these genes happened to produce dwarfism.

Lack of height wasn’t the only reason why these people built smaller houses. Having a tiny home meant fewer building materials were required, which was convenient as domestic animals large enough to pull wagons were scarce and proper roads were limited. So locals had to carry all supplies by hand for kilometers. Smaller houses were easier to heat and cool than larger ones, and blended in more easily with the landscape, making them harder for potential invaders to spot.

Photo credit: Hooman Baradaran

In the mid-20th Century, the region saw a spurt in urban development with the construction of roads and access to vehicles allowing Makhunik residents to bring a wide variety of food to their plates such as rice and chicken. Kids grew healthier and taller than their parents, and with improved healthcare dwarfism began to subside.

Most of Makhunik’s 700 residents are now of average height. It has been years since they left their ancestor's Lilliputian dwellings and moved into brick houses. But aside from their homes and their heights, nothing much have improved for these villagers. Life is still harsh, and agriculture poorer, thanks to continued drought. The younger people go to nearby cities for work and women do some weaving. Older residents rely on government subsidies.

Makhunik’s unique architecture and legacy has a rich potential for tourism, which the residents hope would one day create opportunities for jobs and business in the village.

Photo credit: Mohammad M. Rashed

Photo credit: Mohammad M. Rashed

Photo credit: monji12info/Twitter

Photo credit: Nezare/Twitter

Photo credit: tripyar.com

Photo credit: monji12info/Twitter

In a remote corner in Iran’s South Khorasan Province, near its border with Afghanistan, is a village that, until about a century ago, was inhabited by people of very short stature. Indication of their dwarfism is found in the local architecture. Of the roughly two hundred stone and clay houses that make up the ancient village, seventy or eighty of them are of exceptionally low height. These adobe dwellings are less than two meters tall with narrow doorways that cannot be entered without stooping. Some of these houses have ceiling as low as 140 cm.

Marriages between close relatives, poor diet and drinking water laced with mercury had left the residents of Makhunik a good half a meter short than the average height of that time.

A boy stands in front of a tiny house in the village of Makhunik, in Iran. Photo credit: tripyar.com

For centuries, Makhunik’s ancestors lived in almost complete isolation from modern civilization. The region was dry, desolate and barren that made growing crops and keeping animals difficult. Turnips, grain, barley and a date-like fruit called jujube constituted the only farming. People survived on simple vegetarian dishes such as kashk-beneh (made from whey and a type of pistachio that is grown in the mountains), and pokhteek (a mixture of dried whey and turnip).

Malnutrition contributed significantly to the residents’ height deficiency. The isolation also forced people to marry among close relatives allowing bad genes shared by both parents to be expressed more pronouncedly in their offspring. Some of these genes happened to produce dwarfism.

Lack of height wasn’t the only reason why these people built smaller houses. Having a tiny home meant fewer building materials were required, which was convenient as domestic animals large enough to pull wagons were scarce and proper roads were limited. So locals had to carry all supplies by hand for kilometers. Smaller houses were easier to heat and cool than larger ones, and blended in more easily with the landscape, making them harder for potential invaders to spot.

Photo credit: Hooman Baradaran

In the mid-20th Century, the region saw a spurt in urban development with the construction of roads and access to vehicles allowing Makhunik residents to bring a wide variety of food to their plates such as rice and chicken. Kids grew healthier and taller than their parents, and with improved healthcare dwarfism began to subside.

Most of Makhunik’s 700 residents are now of average height. It has been years since they left their ancestor's Lilliputian dwellings and moved into brick houses. But aside from their homes and their heights, nothing much have improved for these villagers. Life is still harsh, and agriculture poorer, thanks to continued drought. The younger people go to nearby cities for work and women do some weaving. Older residents rely on government subsidies.

Makhunik’s unique architecture and legacy has a rich potential for tourism, which the residents hope would one day create opportunities for jobs and business in the village.

Photo credit: Mohammad M. Rashed

Photo credit: Mohammad M. Rashed

Photo credit: monji12info/Twitter

Photo credit: Nezare/Twitter

Photo credit: tripyar.com

Photo credit: monji12info/Twitter

Makhunik: The Village of Dwarves

4/

5

Oleh

Chandu Numerology