The Devil’s Corkscrews

In the mid-1800s, ranchers across Sioux County, in the US state of Nebraska, began unearthing strange, spiral structures of hardened rock-like material sticking vertically out of the ground. The spirals were as thick as an arm and some of them were taller than a man. Not knowing what they were, the ranchers began calling them “devil’s corkscrew.”

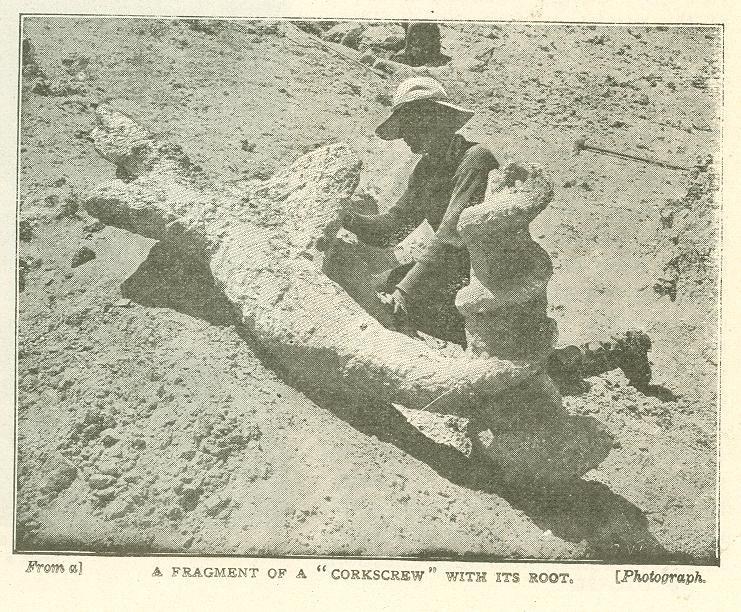

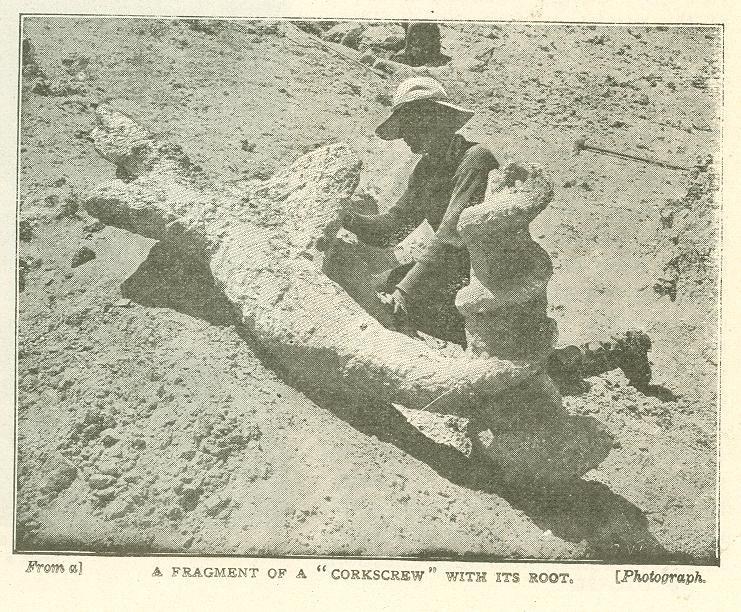

The puzzling structures first came to the notice of the scientific community through geologists Dr. E. H. Barbour in 1891, when he was asked to investigate a nine-foot long specimen that a local rancher had discovered on his property along the Niobrara River. Barbour found that the spirals were actually sand-filled tubes with the outer walls made of some white fibrous material. Barbour knew they were fossils but of what he wasn’t sure. He named them Daemonelix, which was just the Latin equivalent of its local name, devil’s corkscrew.

Nuroanatomist Frederick C. Kenyon stands next to a Daemonelix burrow, discovered in the late 19th century at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument.

The year following the discovery, Barbour put forward his first theory. The fibrous material of the screws provided him the first clue, while the ancient geological history of the surrounding, where these screws were found, provided him the second. Barbour decided that Daemonelix must be the roots of a giant freshwater sponge that thrived in immense freshwater lakes that once supposed to have covered this region.

For a while, the theory held sway but one thing that confounded the scientific community at the time was the presence of rodent bones inside the corkscrews. Further research also revealed that the rocks surrounding the Daemonelix fossils had more in common with semiarid grassland rather than with lakes, prompting Barbour to suggest that the spirals were a new type of giant plants instead. But it was the rodent bones that finally undid the fossil plant theory.

In 1893, Edward Drinker Cope and Theodor Fuchs independently proposed that the Daimonelix were the remnants of ancient spiral burrows that filled up with sand and silt. The bones found within the corkscrews belonged to the rodents who dug them and became entombed within. But Barbour wasn’t going to give up on his fossil plant theory just as yet. He argued that the form of the corkscrew was too perfect to have been constructed by a 'reasoning creature'.

The dispute ended with the discovery of scratch marks on the inside of the spirals indicating that an animals had clawed them out of moist soil. In 1905, the animals responsible for the creation of the corkscrews were identified as the now extinct genus of beavers named the Palaeocastor that lived in the North American Badlands some 22 million years ago.

The Palaeocastor were about the size of woodchucks or smaller. They had short tails, small ears and eyes, like gophers, but long claws and unusually long front teeth which grew rapidly to counteract the wear that results from digging. Evidence suggests that the burrowing beaver fixes its hind feet on the axis of the spiral and literally screws itself straight down into the ground. A couple of feet underground, the burrow extends into several side chambers for sleeping and rearing the young. Some of these living chambers contain low pockets that may have served as sinks for water or dedicated latrines. Some burrows also contain highly inclined living chambers which may have kept the sleeping Palaeocastors safe from flooding.

The spiral nature of the burrow might have provided protection against predators who couldn’t have reached down as they might have into a straight burrow. The spiraling structure could have also made it easier for the Palaeocastor to push excavated dirt up a gently sloping spiral than a steeper straight burrow.

The Palaeocastors died out during the Oligocene Epoch when the planet’s ecosystem changed from a wetter climate to a dry tropical world dominated by grasslands.

Today, you can visit Agate Fossil Beds and hike down the Daemonelix Trail to see for yourself several Paleocastor’s corkscrew burrows still embedded in the side of the hills.

Daemonelix burrows at the Nebraska State Museum of Natural History. Photo credit: James St. John/Flickr

Photo credit: www.digitalhistoryproject.com

Photo credit: www.digitalhistoryproject.com

Photo credit: www.digitalhistoryproject.com

Photo credit: www.digitalhistoryproject.com

Fossil of Palaeocastor. Photo credit: Ghedoghedo/Wikimedia

This fossil depicts a beaver in natural cast of the burrow it had made. Photo credit: Claire H/Wikimedia

Sources: Wikipedia / Natural History Magazine / NPCA / Earth Archives

Subscribe to our Newsletter and get articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

In the mid-1800s, ranchers across Sioux County, in the US state of Nebraska, began unearthing strange, spiral structures of hardened rock-like material sticking vertically out of the ground. The spirals were as thick as an arm and some of them were taller than a man. Not knowing what they were, the ranchers began calling them “devil’s corkscrew.”

The puzzling structures first came to the notice of the scientific community through geologists Dr. E. H. Barbour in 1891, when he was asked to investigate a nine-foot long specimen that a local rancher had discovered on his property along the Niobrara River. Barbour found that the spirals were actually sand-filled tubes with the outer walls made of some white fibrous material. Barbour knew they were fossils but of what he wasn’t sure. He named them Daemonelix, which was just the Latin equivalent of its local name, devil’s corkscrew.

Nuroanatomist Frederick C. Kenyon stands next to a Daemonelix burrow, discovered in the late 19th century at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument.

The year following the discovery, Barbour put forward his first theory. The fibrous material of the screws provided him the first clue, while the ancient geological history of the surrounding, where these screws were found, provided him the second. Barbour decided that Daemonelix must be the roots of a giant freshwater sponge that thrived in immense freshwater lakes that once supposed to have covered this region.

For a while, the theory held sway but one thing that confounded the scientific community at the time was the presence of rodent bones inside the corkscrews. Further research also revealed that the rocks surrounding the Daemonelix fossils had more in common with semiarid grassland rather than with lakes, prompting Barbour to suggest that the spirals were a new type of giant plants instead. But it was the rodent bones that finally undid the fossil plant theory.

In 1893, Edward Drinker Cope and Theodor Fuchs independently proposed that the Daimonelix were the remnants of ancient spiral burrows that filled up with sand and silt. The bones found within the corkscrews belonged to the rodents who dug them and became entombed within. But Barbour wasn’t going to give up on his fossil plant theory just as yet. He argued that the form of the corkscrew was too perfect to have been constructed by a 'reasoning creature'.

The dispute ended with the discovery of scratch marks on the inside of the spirals indicating that an animals had clawed them out of moist soil. In 1905, the animals responsible for the creation of the corkscrews were identified as the now extinct genus of beavers named the Palaeocastor that lived in the North American Badlands some 22 million years ago.

The Palaeocastor were about the size of woodchucks or smaller. They had short tails, small ears and eyes, like gophers, but long claws and unusually long front teeth which grew rapidly to counteract the wear that results from digging. Evidence suggests that the burrowing beaver fixes its hind feet on the axis of the spiral and literally screws itself straight down into the ground. A couple of feet underground, the burrow extends into several side chambers for sleeping and rearing the young. Some of these living chambers contain low pockets that may have served as sinks for water or dedicated latrines. Some burrows also contain highly inclined living chambers which may have kept the sleeping Palaeocastors safe from flooding.

The spiral nature of the burrow might have provided protection against predators who couldn’t have reached down as they might have into a straight burrow. The spiraling structure could have also made it easier for the Palaeocastor to push excavated dirt up a gently sloping spiral than a steeper straight burrow.

The Palaeocastors died out during the Oligocene Epoch when the planet’s ecosystem changed from a wetter climate to a dry tropical world dominated by grasslands.

Today, you can visit Agate Fossil Beds and hike down the Daemonelix Trail to see for yourself several Paleocastor’s corkscrew burrows still embedded in the side of the hills.

Daemonelix burrows at the Nebraska State Museum of Natural History. Photo credit: James St. John/Flickr

Photo credit: www.digitalhistoryproject.com

Photo credit: www.digitalhistoryproject.com

Photo credit: www.digitalhistoryproject.com

Photo credit: www.digitalhistoryproject.com

Fossil of Palaeocastor. Photo credit: Ghedoghedo/Wikimedia

This fossil depicts a beaver in natural cast of the burrow it had made. Photo credit: Claire H/Wikimedia

Sources: Wikipedia / Natural History Magazine / NPCA / Earth Archives

Subscribe to our Newsletter and get articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

The Devil’s Corkscrews

4/

5

Oleh

Chandu Numerology